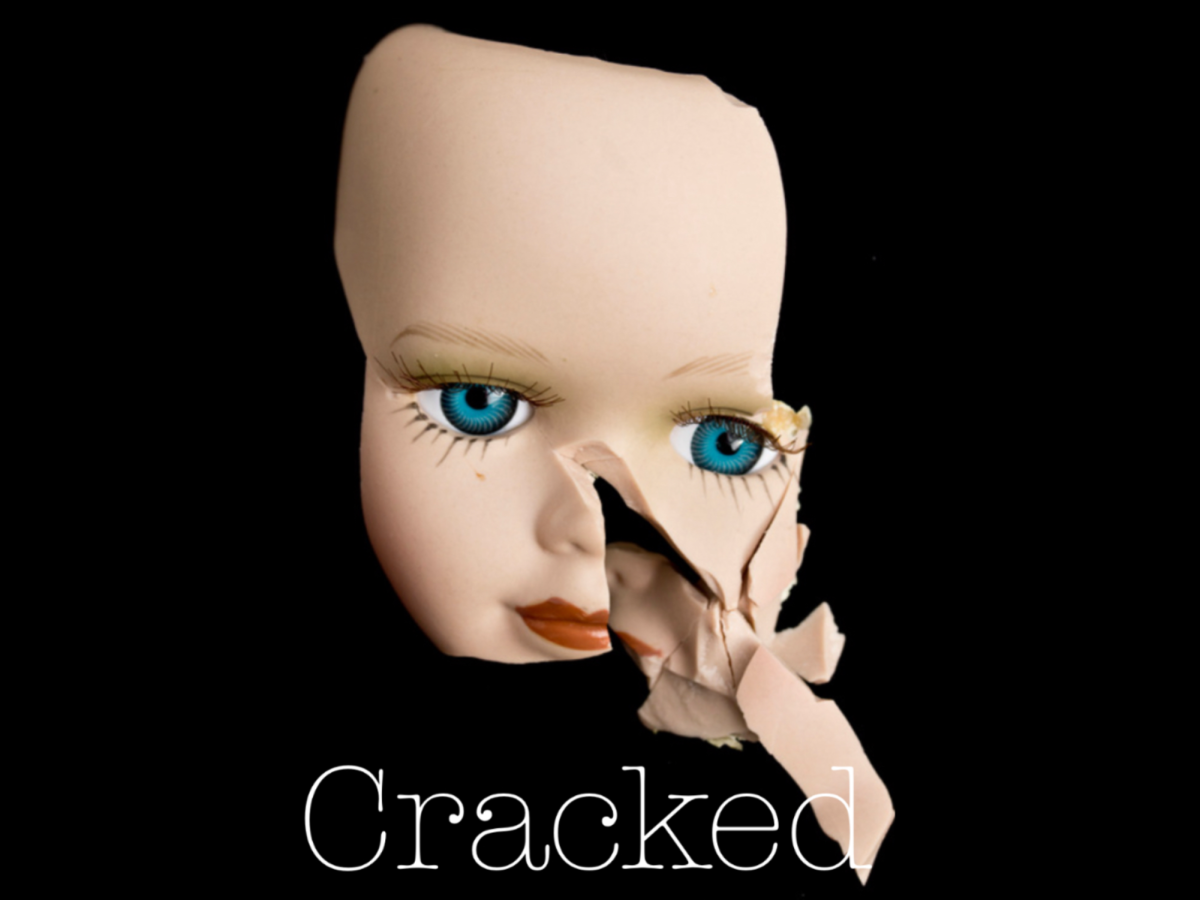

(Experiment: 027 | Status: Experiment Failed | Case File: 027)

Case File 134: Andrew F. Wilson

Age: 26

Experiment Length: 6 years

Age of Conclusion: 32-33

Physical Profile:

Hair Color: Brown

Hair Type: Wavy

Eye Condition: DAMAGED, Heterochromia & Astigmatism

Eye R1: Brown, 20/120

Eye L2: Green, 20/90

Height: 185.4 Centimeters

Weight: 77.1 Kilograms

Build: Average

Body Type: Mesomorph

Muscle Mass: 24%

Body Mass: 16.7%

Beginning Psych. State: Stabilized

Ending Psych. State: Sanity Lost

Extra Items Provided:

(1) Notebook

(1) Bunk Bed

(2) Pillows

(4) Blankets

(12) Plain T-Shirts

(12) SweatPants

(14) Boxer Briefs

(14) Pairs of Socks

(1) Laptop

(1) Guitar

(1) Keyboard

(16) Studio Equipment

(12) Cables

(90) Maintenance Supply kits

(5) Spaceship Repair Manuals

…Inventory Status: Complete

…Experiment Start Status: Primed & Ready To Complete

…Experiment End Status: Failed

Entry #0 | Status: Before Boarding | 5 November 2096 (10:01 AM)

Hello, this is my first day in the space-center for a 6-year psychological experiment. The “lift-off” time is around 12:32 PM. They’ve given me limited items of comfort, a journal was one of the things I was given.

I’m Andrew, and I’m currently 26 years old; I’m majoring in music related things, and psychology. My goal is to graduate and hopefully help people in the future. This study pertains to a condition called “Chronic Loneliness” and it surrounds the feebleness in said disorder. That is one of the many focuses in this study. I’m meant to take strange drugs and journal each day I am in space in great detail.

The company NASA and my University have decided to partner up in order to run this experiment. If I complete this, I get the rest of my years alive, supported and financially covered. I’m in a tough spot, with lots of debt, so I accepted. I’m not allowed to speak, nor have any contact with humans for 10 years. They want to break the “fourth wall” in the feeble human mind. I also accepted, because there’s not much in this world for me. I think I can handle possible brain shrinkage, death, or anything of that sort.

They have cameras, microphones, and machines hooked up around the ship and inside of my body. They did this weeks prior to the experiment. Most of these are to make sure I follow their strict rules:

- ONLY eat the food you are supplied with (If rations are LOW do NOT leave the ship in search of food; unknown creatures do indeed lurk)

- DO NOT terminate any life of any kind (animal, plant, etc.)

- You CANNOT talk to ANYONE at any given time or the experiment has failed

- You CANNOT leave the ship unless instructed to

- You MUST put on your space gear properly (poor cooperation to those instructions may lead to death)

- You MUST use the chamber of sensory deprivation TWICE in a given day (90 minute periods)

- If you terminate this experiment you should have been given and understand the consequences (asylum placement; highly likely)

- You MUST report any ideations pertaining to your life/safety

- You MUST report any hallucinations or anomalies inside of the ship

- You MAY NOT use the technology given to you to communicate with anyone outside of NASA’s monthly private email system

- You MUST take the medication the robot hands to you each day, it is important to maintain your sanity that way

- Falsely taking medication or faking ingesting it may result in penalty if not full termination from the experiment

- You MUST be asleep by 12AM each night, so that the cameras may monitor your sleep for a minimum of 8 hours

- The technology inside and outside of your body is important, patient removal of such technology will be penalized

- Before you sleep you must make sure each radio-wave patch is connected to the proper place on the body in order to monitor your vitals and brain waves during slumber

- DO NOT make any noise above 80 decibels; If you must scream or cry there is a noise-resistant chamber

- DO NOT do any maintenance on the ship without reading through the manuals necessary to repair the ship

- DO NOT use the shower for longer than 25 minutes during each shower session

- It is recommended that you participate in normal hygienic, and exercise routines. This is in order to bring your survival rate to a higher point than it already is

- It is recommended you eat ONLY 2 FULL meals in a given day; breakfast & dinner (snacks are permitted)

- PLEASE continue as if you are living normally in order to maintain your sanity; trick your mind into believing this is how you’ve always lived (the risk of mental crisis or what most call “snapping” is lowered that way)

- If you DO NOT survive due to loss of sanity, suicide, mental torture, etc. you may not have any living family sue

The rules are oddly specific. They’ve also changed between when I read the draft I was sent originally and the sheet I was given while I wait to be loaded onto the ship. You’re probably wondering where I’m going to reside, it is a small colony on Kepler-452b. There are no other people doing this experiment with me. The people on said planet are for spaceship or bodily emergencies. Those pertain to if I say I’ve hurt myself, or if my ship malfunctions and I’m left without oxygen. Even in that event, we are still not permitted to talk to one another. They’re placing me here because it is the closest planet to earth (it simulates similar moon, daylight cycle, weather, etc.).

Entry #1 | Status: “Lift Off” | 5 November 2096 (12:47 PM)

Since I last wrote, I’ve been fully transferred onto the ship, and I am in control of this lift off. There’s something surreal about stepping into a spacecraft, knowing it’s going to carry you beyond the pull of Earth’s gravity. I felt like I was walking into a portal—one that looked unlike anything I expected. The interior of the ship is sleek and futuristic, but it caught me off guard how different it is from what you see in movies. For one thing, the entire interior is black—jet black—which is strange considering almost every ship I’ve ever seen on TV or during training was white or metallic. I remember asking about it before the transfer, and one of the engineers smirked, saying something about how “black absorbs heat better and looks cooler anyway.” Yeah, real scientific.

The ship itself has this gallery-style living space that feels both compact and cozy, but there’s no mistaking it for luxury. Everything has its purpose—a no-nonsense design meant for survival and efficiency. Against one of the walls, there’s a bed, or at least something that resembles one. It’s anchored to the wall with industrial-looking straps to keep me in place as I sleep—no floating away in zero-g here—and a set of blankets to keep me warm, though I imagine I’ll be tangled in those straps more often than not. There’s also a small station for cooking freeze-dried food packets, which NASA made sure I was well-practiced with. I’ve got a fridge to store those packets, which feels almost comical because it’s roughly the size of a shoebox. But hey, when you’re hundreds of miles above Earth, even something as simple as cold food feels like a luxury. A small, oddly cute counter juts out from the wall, just big enough for me to plate my food and eat. I’m not expecting five-star meals up here, but I’ll take anything over starving.

The back of the ship is divided into two smaller rooms, and I use the word ‘rooms’ loosely—these are little more than glorified closets. On the left is the bathroom I’ll be using for the duration of my stay. Surprisingly, it’s spacious—well, spacious by spaceship standards anyway. There’s a toilet, a sink, and even a shower. I can already hear people back home asking, “How does a shower work in space?” The answer: it doesn’t work like back home. Water doesn’t fall here. Instead, I’ve got special sponges soaked in pre-treated water, and I’ll be scrubbing myself down with those. It’s not glamorous, but it’s better than going weeks without bathing.

On the right is what NASA calls the “generator room,” but it’s more like the heart of the ship. It’s where all the critical systems are housed—power, oxygen generation, all that life-saving stuff. I’ve been told that maintenance there will be rare, but if something goes wrong, it’s my job to troubleshoot. I’m not exactly a mechanic, but I’ve been trained to handle basic malfunctions. The last thing I want is to be the guy floating through space when the lights go out or the oxygen runs thin.

I know what you’re probably asking by now: “Why is this guy rambling about the ship? Does he even know how to drive it?” First off, yes—of course I know how to drive this thing. I’ve been trained for years for this exact moment.

While most of the ship’s systems are controlled remotely by NASA back on Earth, I’m the human backup. I’m trained in steering, activating the thrusters, and just about everything else you can think of when it comes to this ship. It’s like driving a car with autopilot—sure, it mostly does the work, but I’m here to take over if the computer decides to have a bad day. My primary responsibility is launching the pre-programmed systems, but if anything happens that the code can’t account for, that’s when I step in. I guess you could say I’m NASA’s insurance policy—a flesh-and-blood failsafe.

And let’s not kid ourselves—a lot can go wrong. I’m heading to a whole other colony in space, and there are so many things that could turn sideways at a moment’s notice. NASA has entire teams working around the clock—13-hour shifts—just monitoring my ship and my trajectory. My department alone has dozens of people glued to their screens, checking every little fluctuation in the data. It’s weird knowing that there are more eyes on me now than there have ever been in my entire life. I’m alone on this ship, but at the same time, I’m not. It’s this strange paradox that I don’t think I’ve fully wrapped my head around yet.

Still, as I sit here in the pilot’s seat, staring out through the window—or, rather, the viewport—it’s hard not to feel a mix of awe and nerves. Earth is shrinking in the distance, a blue marble surrounded by endless black. I can feel the hum of the ship around me, the quiet whir of the systems doing their job, and for a moment, I think about everyone I left behind. My family. My friends. The people who probably think I’m crazy for signing up for this mission. Maybe they’re right. Maybe you’ve got to be a little bit crazy to volunteer to leave the planet, to be alone in a black ship drifting through an infinite void. But here I am. And as the thrusters roar to life, I take a deep breath and grip the controls, ready for whatever comes next.

Because this isn’t just about getting to the colony or fulfilling some scientific mission. This is about proving something to myself—that I can do this. That I’m capable of handling whatever space throws at me. And even though I’ve been trained, tested, and prepped for years, the real test starts now.